Technology is forcing militaries everywhere to confront an uncomfortable reality. The recent Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and developments in Ukraine, Syria and Yemen have shown that even simple and perhaps only partial adoption of uncrewed systems and loitering munitions can allow potential adversaries to strike deep and unannounced, rendering traditional notions of territorial advantage and occupation increasingly less relevant, even for a well-equipped force. New sensors and processing mean that traditional options like camouflage and movement at night now offer only limited protection. Widespread availability of increasingly capable systems means we can expect to see similar challenges in most places UK forces might need to operate. And it won’t just be traditional militaries who can pose such a challenges, militias and insurgents will be able to acquire similar systems. The size and disposable nature of the air vehicles being used means regular air defence options are often not effective. And there are also challenges in tackling similar trends in uncrewed ground and maritime systems.

A new urgency but an old imperative

The struggle for advantage, the competition to find a military edge is universal and such is the pace of technological change, something we witness in our everyday lives, that new developments are coming thick and fast. The global investment in artificial intelligence technologies is accelerating this, forcing us to be agile in adapting and adopting new approaches, new operating concepts and new systems.

In some ways, the traditional military drive for speed of operations (tempo), to protect one’s own forces and to achieve mass at just the right place and time are eternal, unchanged. It’s just the means by which this is achieved and the speed of developments. All this new technology offers significant opportunity to find a ‘winning edge’, its just that the other side is trying to achieve a similar thing.

A focus on advantage through teaming with technology

It is this challenge, the need to find advantage, to get ahead of our adversaries through new and emerging technology that the recent UK Integrated Review focused on, with an increased emphasis on science and technology. And centre stage was the need to harness artificial intelligence and its disruptive combination with uncrewed and swarming systems. Finding this new technology and exploring its application is a key part of Dstl’s role and within the Dstl programme are a range of projects that are seeking out new ideas and potential game changing innovations. The Human Autonomy Teaming for Adaptive Systems project (HATAS) is just such a Dstl funded flag-ship project, tasked with bringing together and testing combinations of these technologies.

HATAS recognises the crucial importance of getting the timely interactions between human and technology right. Get it wrong and the soldier, sailor or airman is overloaded, distracted or otherwise cannot unlock the advantage offered. Multiple inputs compete for their time and attention, and they can ill afford to focus on reaching for hard to access information or making sense of a torrent of data, never mind actually controlling the more routine activities of an army of uncrewed systems.

But what do we mean by human autonomy teaming?

HATAS is a recognition that we need to prepare for a time beyond humans working with relatively simple machines; machines that are currently limited to basic functions such as avoiding obstacles or executing a simple plan. Greater autonomy in the truest sense means systems that are able to adapt to situations, to make rapid decisions and even anticipate. Teaming these systems, and lots of them, with the human operator is the target. For it is the human who needs to direct and control and who will still own the difficult decisions involved with the application of military force.

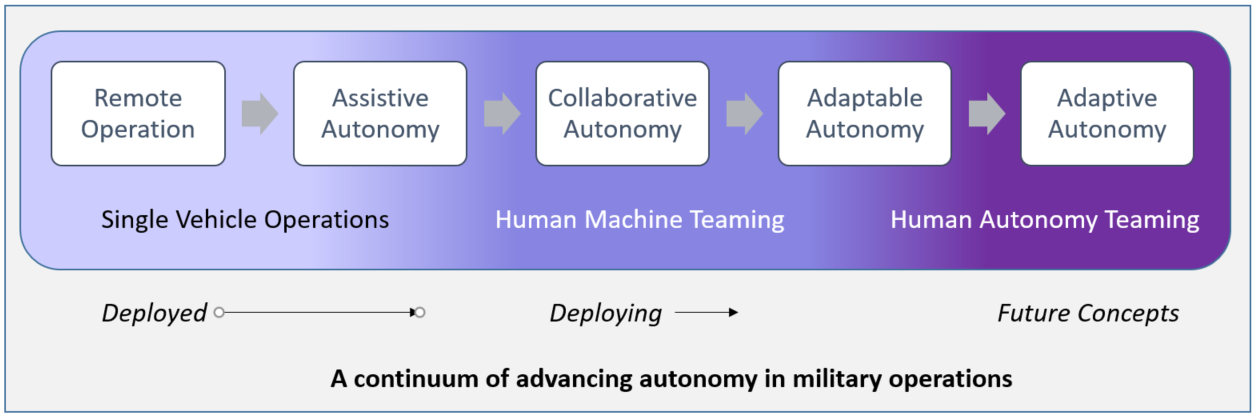

In essence, we are seeing progress on a continuum from remotely piloted systems, to systems with increasing support to the operator (akin to the features on a modern car), to increased delegation to semi-autonomous uncrewed systems, operating collaboratively and in groups, dynamically teaming with different operators across the battlespace. This ‘human machine teaming’, supported by adaptable or adjustable autonomy, is the current destination. But in the generation after next, with pervasive AI and much more adaptive systems, the continuum will step still further into what is referred to as ‘human autonomy teaming’. It is this step we need to be ready for.

Our focus on preparing for a HAT future

HATAS will put uniformed service men and women and Dstl scientists in the loop, allowing them to develop and understand cutting edge concepts in a range of operational contexts. The programme is now assembling contributions from established players and new entrants to the world of defence, readying for an iterative programme of development and assessment. Led by Dstl and QinetiQ and contracted through the Serapis framework, the project features Diem Analytics, Montvieux and Thales. The aim is to draw in more inputs from other participants as the project progresses and to use a mix of table top, synthetic and ultimately live experimentation. By carefully analysing results, we hope to progressively refine and mature options for further exploitation in other Defence progammes, themselves likely to be agile developments. Success is deployment of the learning and the technologies into generation after next military capability.

Our plan is to have regular updates, to showcase some of the ideas and the contributions from the programme partners and to use these communications to draw in new inputs. We also hope to feature inputs from end users on their hopes for the programme and observations on some of the challenges and opportunities.